By Dori Jones Yang

Confession: I am not a Chinese boy living in 1870s Connecticut. I was not alive in the 1870s. I have never lived in Connecticut. I am not a boy. And I am not Chinese. Whew! Got that off my chest.

We writers of historical fiction are called to help readers imagine life in a different era than our own. To face this challenge, we do all the research we can—reading books written about the era and examining letters and books written at the time. We take note of the kind of clothing people wore, their food and drink, the style and decor of their homes, and even their modes of transport. We ask the questions: what were the big events of the time? What were common attitudes among different classes of people?

Then, we let our imaginations take over. What might it have felt like to live at that time? How might such a person have responded to common—or uncommon—events? Fiction gives us license to use our imaginations in ways that non-fiction writers don’t have.

The toughest question, though, comes when a writer chooses to recreate the experience and feelings of someone of a different race or culture. What right does a Caucasian American woman like me have to pen a novel from the perspective of a young Chinese boy? Born in Ohio, how could I dare to write a book about how it feels to be a foreigner in America? Shouldn’t I stick to writing solely from the viewpoint of a person just like me?

I get it. White authors have been writing about people of other ethnicities in America for hundreds of years, often misrepresenting them. The subservient characters of Mammy and Uncle Tom. The tragic Asian heroine who conveniently dies at the end, as in Madame Butterfly and Shogun. The tale of self-sacrificing Pocahontas. Even though we are sensitive of stereotypes to avoid, white authors run a risk of misrepresenting viewpoints each time we write about someone of a different background.

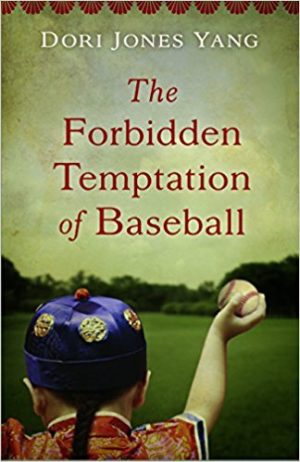

Yet, I continue writing novels in which the main character is Chinese. My newest book, The Forbidden Temptation of Baseball, is about two Chinese brothers who were sent to Connecticut by the Chinese Emperor in 1875. It’s the fourth book I’ve written from a Chinese point of view.

Why do I keep on? Because these perspectives are part of the patchwork of the American experience. If American kids read stories from many different cultural backgrounds, they will have a better understanding of the diversity of experience and lives in our country and around the world. Reading novels about children from other cultures will help our children be more open and accepting of people who come from backgrounds different from their own.

I learned this first hand. While studying Mandarin in Singapore, I felt the frustration of living as a minority in a foreign land and struggling to express my thoughts in the language of those around me. Later, I lived and worked in Hong Kong, traveling widely throughout China, befriending many Chinese people from different backgrounds, hearing many incredible stories that ached to be told. On a personal note, my husband is Chinese, and we have raised our daughter immersed in Chinese culture, here in the United States. Listening to my daughter’s response to growing up Asian in America and meeting her friends of many different races and backgrounds, I widened my own understanding.

For me, writing from the perspective of Asian characters is an act of conscience. I want to do what I can to counter stereotypical points of view. For instance, many of the earliest Chinese immigrants to America came to do hard labor in the gold mines, railroads, and factories on the West Coast. That’s true. But that led to a backlash of anti-Chinese sentiment among Americans and a long-held assumption that all Chinese immigrants were low-wage “coolies.” When I found out that more than a hundred Chinese boys came to the United States to study in that same era, their story offered a different narrative. Many of these students got into excellent colleges. Their experience, an under-told story, more closely fits that of many recent Chinese immigrants.

I believe very strongly that in this day and age especially, it’s important for Americans to try to understand the mindset of how it feels to be a foreigner in our society. Especially kids. In American schools, kids are very likely to be studying with classmates born in a different country. Unfortunately, some react by bullying and teasing. How much better to read a book and try to understand how alienated the classmates might feel, surrounded by unfamiliar words, values, and assumptions! Books I recommend include Thanhha Lai’s Inside Out and Back Again, Cynthia Kadohata’s Kira-Kira, and Bette Bao Lord’s In the Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson.

I think it’s healthy for American children to connect with the perspective of people from other countries, cultures, and races. If they learn empathy as children, perhaps they will grow up to be more sensitive and understanding to the plight of others. The more diverse books American children read, the more hope there is that America, in the future, will be a strong neighbor and a more welcoming country.

I agree that there is a need for authors of all ethnic and racial backgrounds to come forward and share their stories. I fervently hope the children’s book publishing industry will proactively seek out writers from diverse backgrounds. In the meantime, writers like me have the unique opportunity to help immerse readers in culture, ways of living and thinking, and experiences that are new or foreign to them.

If I could learn empathy and understanding from my experiences, I hope my writing can have that effect on my readers.

DORI JONES YANG is a former Business Week bureau chief in Hong Kong and author of seven books, including her newest, The Forbidden Temptation of Baseball (SparkPress, August 15, 2017). Dori lives in Kirkland, WA. More at www.booksbydori.com.